As I mentioned earlier, I'm teaching Physics at a new-ish high school this year. I've been spending a large chunk of time designing the curriculum and materials for this class. So far, the year has been a bit hectic (thus the lack of posts here), but the school community is really amazing, supportive, and progressive. A few things that are making what can be a difficult first year much better than average:

- Experts at my fingertips & time to develop curriculum. The curriculum people at my new school were very proactive in trying to connect me to experienced physics teachers. I was (and continue to be) impressed with the level of support they're providing for teachers developing new curricula. Unfortunately, none of the teachers had used Modeling Instruction. Fortunately, I've curated a twitter feed that includes 15-20 active modelers and I've found countless helpful resources from those very helpful people. We've also had dedicated time to work on curriculum development. Besides a (paid) week in June, we've also been given time during our professional development time to simply work on building the curriculum. As someone new to the school developing the curriculum for a class that has never before been offered at this school, this has been invaluable.

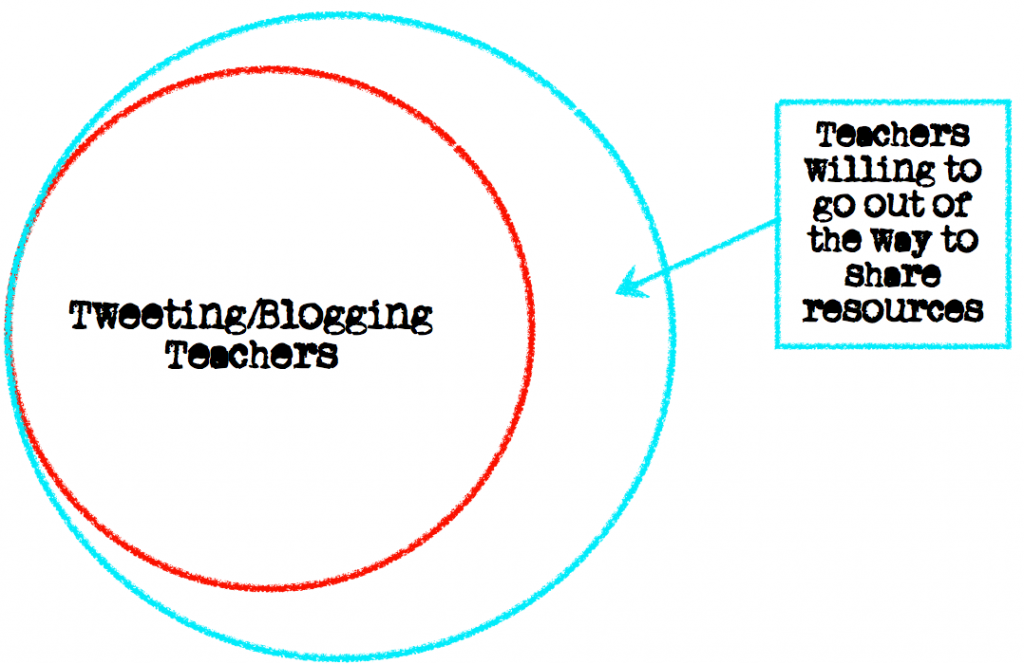

- The willingness to help a n00b. Here's a Venn Diagram showing Teachers using Twitter/Blogs and Teachers willing to help out a poor Modeling Instruction rookie who wasn't able to make it to a Modeling Workshop this summer due to his crazy schedule:

Perhaps this shouldn't be surprising- I mean, if someone is actively spending time writing a blog or sharing via twitter they're more than likely into the whole "sharing" thing. I'm sure I've asked (and will continue to ask) more than my share of dumb questions. Amazingly, despite my frequent questions that surely induce heavy eye-rolling on the other side of the Internet, I've continued to receive an amazing amount of help with zero snark (and zero snark when we're talking about The Tweeter is nothing to shake a stick at!). - The huge resource of online materials. I chose Modeling Instruction as the curriculum for my Physics classes because I believe in the process it supports- not because it's the easiest to design and implement. To be honest, it's a bit scary (especially because I couldn't get to a Modeling Workshop prior to implementation). However, there is no shortage of materials to be found online- and not just general "modeling-instruction-is-great-and-here's-why" materials (there's a lot of that too, though). There are detailed descriptions of labs and their results, handouts, tips for whiteboarding, worksheets, etc., etc., etc.

Here's a partial list:

- The American Modeling Teacher's Association. Yes, you need to be a member to access the resources, but the resources are huge. I shelled out the $250 for a lifetime membership. The materials and support I gained access to for that money is easily worth the $250 by itself.

- Kelly O'Shea's Model Building Posts & Unit Packets. Kelly's an expert modeler. Her posts really helped me first visualize what a modeling classroom looks like. Her materials are also excellent.

- Mark Schober's Modeling Physics. Contains materials and resources for every modeling unit, along with calendars- which was nice as someone new to modeling to get a rough timeline for each unit.

- Todd K's DHS Physics Site. Even more modeling materials and calendars.

- Paying it forward. It's my plan to make the materials I develop and implement for my Physics classes readily available online in some format, at some point. I've gained so much value from the resources others have posted that it is (perhaps with some hubris) my hope that others in the future might gain something from my experience. Obviously I'm no expert- but my hope is that through sharing both the materials and my reflections on how they were implemented will, if nothing else, help me to become a more purposeful and reflective educator.

Perhaps I'm odd, but I really enjoy designing new curricula- which is a lucky break since I'm responsible for designing the Physics curriculum from the ground up. So far it's been a challenge given the specifics of my particular situation (which will undoubtedly be a topic for future post), but as I come to know my students better and gain more experience implementing modeling instruction, I've found the process more and more enjoyable.