HowTo: Have a good advisory

- Eat. Stop at the store. Pick up some donuts, mini-muffins, and assorted fruit. Advisory isn't a fun place for students. Make it more inviting. Bribery through food is a good start.

- Apologize. Mainly apologize for using the "curriculum" you're supposed to be using. Be honest. Tell them you were trying to the the right thing, but some times the "right thing" isn't what's right.

- Talk. This is big. At this point students will most complain about how stupid advisory is and how it could be used for so many more useful things. Complaining is good

- Share. Show a couple video clips you particularly like. Show a couple video clips students like.

- Enjoy. The first advisory meeting you've had all year that wasn't forced or awkward.

Advisory (a.k.a. mentor/mentee, homeroom, seminar, etc.) is designed to be a time where students meet with a teacher to form a relationship outside of the traditional teacher/student interactions. Teachers meet with the same group of students for all four years of high school with the expectation that deeper and more lasting relationships will be formed between students and teacher. I believe that a well executed advisory can be a positive influence on school culture and student success. However, our system is broken.

In a nutshell, here are the major problems:

- We meet with our advisories every two weeks for 30 minutes. This isn't enough to form lasting relationships.

- Activities and "curriculum" used for advisory are developed on an "as-we-go" basis. There just isn't time to develop this stuff on the fly.

- A small, under-attended, over-stressed committee of five or six individuals designs the "curriculum" that is used for advisory. Six simply isn't enough people to tackle this monumental task.

- All levels use the same "curriculum" materials. All grade levels- and especially freshman and senior levels- should have their own goals and activities.

Today, I quit. I stopped using the materials provided. I stopped using any formal materials. I couldn't put my students or myself through that uncomfortable hell of pushing through an activity that neither of us thinks is appropriate or helpful.

If you had been visited my classroom during this time you wouldn't have been blown away by anything that happened. If you had been in my classroom for every other advisory to see the awkward and forced interactions that used to be the norm you'd understand my enthusiasm more clearly.

As educators we want so much for advisory to be valuable that we forget the most valuable part is just getting to know our students. You don't need a formal curriculum for that. You just need time and desire (a few donuts don't hurt either).

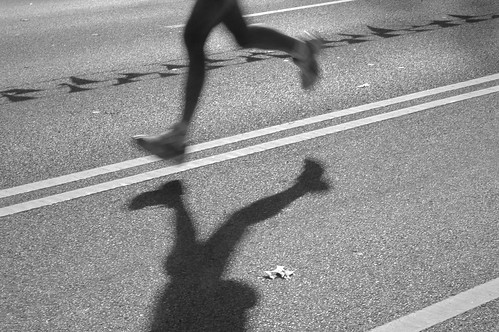

I'm confident that the curriculum I'm using and the way I'm presenting it is at least "good." My frustration comes from knowing that it's not the best. It's the difference between completing a marathon and winning a marathon. Completing a marathon can be pretty a pretty major accomplishment for a recreational runner like myself. However, if you're an elite runner with the talent and training to be able to win a marathon simply finishing isn't a major achievement.

I'm confident that the curriculum I'm using and the way I'm presenting it is at least "good." My frustration comes from knowing that it's not the best. It's the difference between completing a marathon and winning a marathon. Completing a marathon can be pretty a pretty major accomplishment for a recreational runner like myself. However, if you're an elite runner with the talent and training to be able to win a marathon simply finishing isn't a major achievement.

Self-discipline is a trait that generally gets high praise from both progressive and traditional educators. However, Kohn points out that:

Self-discipline is a trait that generally gets high praise from both progressive and traditional educators. However, Kohn points out that: "Learning, after all, depends not on what students do so much as on how they regard and construe what they do."

"Learning, after all, depends not on what students do so much as on how they regard and construe what they do."

The laptop cart: currently hiding in my room

The laptop cart: currently hiding in my room